Farey

The oldest reference is the well known Treatise by John Farey from 1827 (here are some details regarding the author).

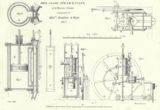

Starting around page 677 Farey describes the Bell Crank Engine detailed. He refers to a table in his book, which I extracted in picture 1.

Some prominent features can be seen really nice. In Fig. 4 the cylinder’s steam jacket is visible (quite like the Smethwick Engine). James Watt finally had given up the use of steam jackets, but now with William Murdoch it is there again. Eventually progress in moulding and casting has caused the change.

Furthermore a section of the valve can be seen and so the name D-Valve is understandable (Farey describes the D-Valve in another chapter detailed, online you may look here for further details).

In Fig. 5 und 6 the steam channels in the cylinder may be seen and the D-valve in front view.

The bell-crank lever is in Fig. 1, as well as the rim (consisting of two circles). You may get an idea of the levers for the valve rod too.

I would like to emphasize some of Farey’s statements:

After James Watt had retired from the daily business, William Murdoch acted as constructing engineer. John Southern carried on as factory manager. Watt junior on one hand and Matthew Boultons only son on the other shared the management of “Messrs. Boulton, Watt, and Co.”.

Most important feature of Murdoch’s patent from 1799 was the D-valve, which made the four valve nozzles and the valve gear used so far obsolete.

There were increasing demands to produce smaller engines (up to 8 h.p.). These engines should not rely on any housing and so no special prerequisites should be necessary for a machine room. Murdoch and Southern created the type of the “Independent Engine”. The cistern became the base for all other parts of the engine.

The piston rod was guided without Watt’s linkage. This was made possible by the large distances and radii.

A considerable number of Bell Cranks were built 5 or 6 years after the end of Watt’s patent [1800] in Soho. There were engines with 4, 6 and 8 h.p.

The engine is called “out of balance”. Experiments have been made to cure this by adding a weight to the flywheel rim - but that failed.

The Bell Crank was last produced 1806 in Soho. A real beam was used again, but the D-valve remained. These engines did not use the building structure any more.

After some improvements the D-valve is now commonly used.

So far Farey.

Dickinson + Jenkins

James Watt and the Steam Engine by Dickinson and Jenkins is a real good reference from my point of view. It is based on a very intense study of letters by Watt, Boulton and others. Henry Winram Dickinson was staff member of the Science Museum since 1895. The Newcomen Society has put further information online.

Dickinson and Jenkins confirm quite a few of Farey’s statements (S. 171 f.). There hardly can be any doubt, that James Watt was not amused by the Bell Crank design. But the sons (James Watt junior on one hand and Matthew Robinson Boulton on the other) had the expiration of the patent 1800 in mind. Furthermore a cost-effective solution for engines with only little power had to be found. William Murdock, since 1777 with Boulton and Watt, got a patent in 1799. The “long D” valve was a cornerstone in the patent. John Southern, who had worked for Watt since 1782, wrote a letter to Watt junior and expressed his concerns to give up the proven beam design.

Dickinson states that five Bell Crank Engines had been built, at least two of them in the special form of a blowing engine. On pg. 172 Dickinson writes:

This was a 6 h.p. engine, and the drawings are dated November 1802. After this the manufacture of bell-crank engines was discontinued and the use of the beam was reverted to for small engines up to the introduction of the side-lever stationary engine, but it does not appear that engines so small as 2 h.p. and 3 h.p. were again produced.

Matschoß

Conrad Matschoß adds one new aspect in his Geschichte der Dampfmaschine: He claims frequently cracked bellcranks as the root cause to revert to the proven beam design. While this can easily be imagined (repeated bending stresses of a big part from cast iron), Matschoß does not give us a reference (as usual).

A preserved Bell Crank Engine

There seems to be only one preserved Bell Crank. This is in the Science Museum London. Unfortunately the museum’s website is not really helpful when it comes to a research. I could find picture 2 without an imprint, but only at a low resolution. The text states that this engine had been built by James Watt and Matthew Boulton, which is plain nonsense (Watt started 1795 to retire from daily business). Another statement says:

This design was used on the paddle steamer ‘Clermont’ in 1805 and also in Boulton and Watt’s Soho works until 1896.

Allen took this picture. In his comment he states, that the engine was made by an unknown manufacturer (By the way: Using the Nearby Search you can find more steam engine pictures Allen took in the Science Museum).

A Bell Crank Engine on the world's first commercially used steam boat ?

Robert Fulton’s Clermont (North River Steamboat) was launched 1807 and was put out of service in 1814. According to Robert H. Thurston a Bell-Crank made by Boulton & Watt was utilized 1 .